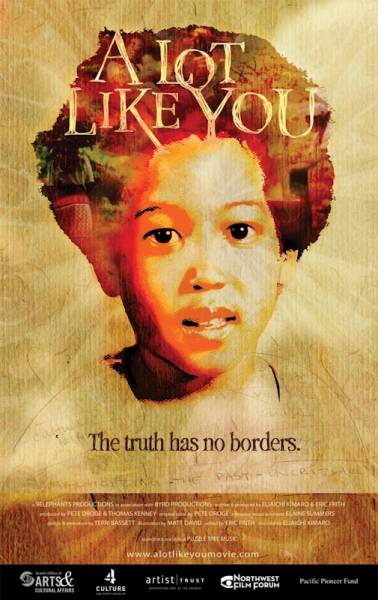

A Lot Like You by Eliaichi Kimaro. A journey beyond culture; into our lives.

When a first generation African-American woman searches into her mutlicultural roots and rediscovers her Tanzanian family.

Perhaps the best way to introduce Eliaichi Kimaro's film A Lot Like You is, as she does herself in the very first minutes of her film, to say what the film is not: it is not a documentary of her Chagga roots.

Although her desire to know more about this Tanzanian tribe, where her father is from, initially motivated this film project, Kimaro quickly reveals that this first attempt miserably failed: she was there, sitting with her camera, filming Chaga elders dancing… But she was no more than a tourist, an African-American tourist, more simply, an American.

A Lot Like You - Official Trailer

How to approach culture ?

Eliaichi Kimaro realized that this desire to know more about her African roots concealed a deeper need to disentangle her multiple identities: she is a first generation African-American married to a White American, her father is from Tanzania, her mother from South-Korea; they grew up in the United States, she was close to her Korean relatives, but when she would return from time to time to Tanzania, she would never really know how to relate to her Chaga relatives.

And so we embark with her on her first film-making journey. With us spectators, she shares her intimate questions, her doubts, her uncertainties, her surprise.

Surprise indeed, for she realizes that it is not so much this thing called "Chagga culture" that she ignores, but that she knows nothing about individual stories, the untold lives of those she called "her family".

Kimaro digs, almost by feel, under what we usually and superficially brand as "cultural" facts. First comes her father's typically postcolonial trajectory: a young man who was one of the "happy few" colonized subjects to get the opportunity to study abroad - and who will, though not easily, learn what it means to "be gone". Then came his love relationship with a South-Korean lady, Kimaro's mother: un unsual encounter for the time, also in the United States still shaken up by the civil rights movement.

When Tanzania became independent, the just-married couple returned. It was not easy, nor natural for these two products of the American dream to adapt to a now socialist-oriented country ruled by the charismatic Julius Nyerere. Kimaro's father, an economist, had to teach Marxist economy in the university of Dar es Salaam… Not for long. He took the first opportunity to go back to the US and work for the controversial-to-be International Monetary Fund (IMF).

We reached here the first layer of the story, that of the young African generation who dreamt voluntary exile as the key to emancipation - but struggled, as many others, to find a place where they would truly belong to, an identity they would be at peace with.

Kimaro films her international-connected parents with a tormented lucidity she is well aware that the identity gap that formed between her father's - and her's as well - American way of life and his Chagga background has also turned into a social and financial gap estranging him from his own family.

Her family album and filmed memories of her comfortable childhood are thus brutally confronted to the harsh routines of his Chaga relatives.

Keeping close to these individual trajectories, she points out the contingency that enabled others to choose their lives - while others found their right to choose confiscated. Confiscated by what, by whom, and when?

The movie then enters into a new dimension. Back to Tanzania, Kimaro organized a family meeting with her father and his siblings. To her surprise, faces were shadowy and unspeakable thoughts filled the air.

It appeared that what kept these siblings united was also everything that separated them: they only shared the same contingency that guided their lives, the contingency typical of colonial disruptions that gave to some the power to choose the direction of their lives, while other remained subjected to seemingly stable cultural practices…

And these take not such an unusual form: that of gender divide.

Kimaro comes to terms with an untold gender bias of the so-called Chagga "culture", or, to speak the truth, that of a trivialized practices of abuse against women.

What an irony for Kimaro had spent ten years of her life counsilling victims of rape and abuse and reveals that she has been herself child sexual abuse. Faithful to her initial quest for her family history she tactfully links her aunt's histories to her's.

The film-maker is suddenly confronted to crucial question: what do you make a movie that reveal untold truths? What do you make of revealing abuse? What do you make of a documentary? And what of we all too easily call "culture"?

She does not gives definite answers to each of these questions. But after all, answers matter less than sharp and critical questions which reveal that the lives of those too often estranged under the obscure concepts of "tribe" or "culture" are, in fact, too complex to be reduced to "documentaries" and all too close to us to be seen as alien.

Finally, A Lot Like You isa very personal film, that could almost be watched as a movie on family souvenirs - but it starks a reflexion on identity and family that goes well beyond its initial, intimate narrative.

Discover the film's website:http://alotlikeyoumovie.com/and don't miss Eliaichi Kimaro's numerous lectures and activities around her film and research:http://alotlikeyoumovie.com/blog/

ZOOM

The Chaga hut and the architecture of our lives

What is this indescribable attraction that brings all those who lived abroad back to their Chagga hut?

No matter how big a US-style village, how big a swimming pool, how green and flowery the garden, how bright and wide the horizon at the beach can be... There was something missing in Kimaro's father: his first house, where he was born, a Chagga hut. Round, hand made, with only one door, the hut is a symbol of Chagga culture and craft, but, most of all, of Chaga families and their history.

Kimaro films the houses of her own life in an intrigued way, questioning how the architecture we live in may impact our lives, and perhaps, how our lifes are prisoners in a way of the house they were bound to.

For houses were not only the realm of the family - it was also the realm of abuse.

Yet again, there is no complacency in her filming the American dream, or a more traditional houses: Kimaro does not seach for authenticity. Rather, she raises one question: to what extent does the architecture in and of our lives really, and for good, shape us? Can we ever escape from it?

Kimaro seems to answer us that the point is not so much to escape than to know how to re-enter into our past houses, and feel comfortable, into our own lives.

Anaïs Angelo